This is a mildly edited transcript of my JSConf Australia talk. Watch the whole talk on YouTube. A sequel to this post is available over here.

Hello, I used to build very large JavaScript applications. I don’t really do that anymore, so I thought it was a good time to give a bit of a retrospective and share what I learned. Yesterday I was having a beer at the conference party and I was asked: “Hey Malte, what actually gives you the right, the authority, to talk about the topic?” and I suppose answering this is actually on topic for this talk, although I usually find it a bit weird to talk about myself. So, I build this JavaScript framework at Google. It is used by Photos, Sites, Plus, Drive, Play, the search engine, all these sites. Some of them are pretty large, you might have used a few of them.

This Javascript framework is not open source. The reason it is not open source is that it kind of came out at the same time as React and I was like “Does the world really need another JS framework to choose from?”. Google already has a few of those–Angular and Polymer–and felt like another one would confuse people, so I just thought we’d just keep it to ourselves. But besides not being open source, I think there is a lot to learn from it and it is worth sharing the things we learned along the way.

So, let’s talk about very large applications and the things they have in common. Certainly that there might be a lot of developers. It might be a few dozens or even more–and these are humans with feelings and interpersonal problems and you may have to factor that in.

And even if your team is not as big, maybe you’ve been working on the thing for a while, and maybe you’re not even the first person maintaining it, you might not have all the context, there might be stuff that you don’t really understand, there might be other people in your team that don’t understand everything about the application. These are the things we have to think about when we build very large applications.

Another thing I wanted to do here is to give this a bit of context in terms of our careers. I think many of us would consider themselves senior engineers. Or we are not quite there yet, but we want to become one. What I think being senior means is that I’d be able to solve almost every problem that somebody might throw at me. I know my tools, I know my domain. And the other important part of that job is that I make the junior engineers eventually be senior engineers.

But what happens is that at some point we may wonder “what might be the next step?”. When we reached that seniority stage, what is the next thing we are going to do? For some of us the answer may be management, but I don’t think that should be the answer for everyone, because not everyone should be a manager, right? Some of us are really great engineers and why shouldn’t we get to do that for the rest of our lives?

I want to propose a way to level up above that senior level. The way I would talk about myself as a senior engineer is that I’d say “I know how I would solve the problem” and because I know how I would solve it I could also teach someone else to do it.

And my theory is that the next level is that I can say about myself “I know how others would solve the problem”.

Let’s make that a bit more concrete. You make that sentence: “I can anticipate how the API choices that I’m making, or the abstractions that I’m introducing into a project, how they impact how other people would solve a problem.” I think this is a powerful concept that allows me to reason about how the choices I’m making impact an application.

I would call this an application of empathy. You’re thinking with other software engineers and you’re thinking about how what you do and the APIs that you are giving them, how they impact how they write software.

Luckily this is empathy on easy mode. Empathy is generally hard, and this is still very hard. But at least the people that you are having empathy with, they are also other software engineers. And so while they might be very different from you, they at least have in common that they are building software. This type of empathy is really something you can get quite good at as you gain more experience.

Thinking about these topics there is one really important term that I want to talk about, which is the programming model–a word that I’m going to use a lot. It stands for “given a set of APIs, or of libraries, or of frameworks, or of tools–how do people write software in that context.” And my talk is really about, how subtle changes in APIs and so forth, how they impact the programming model.

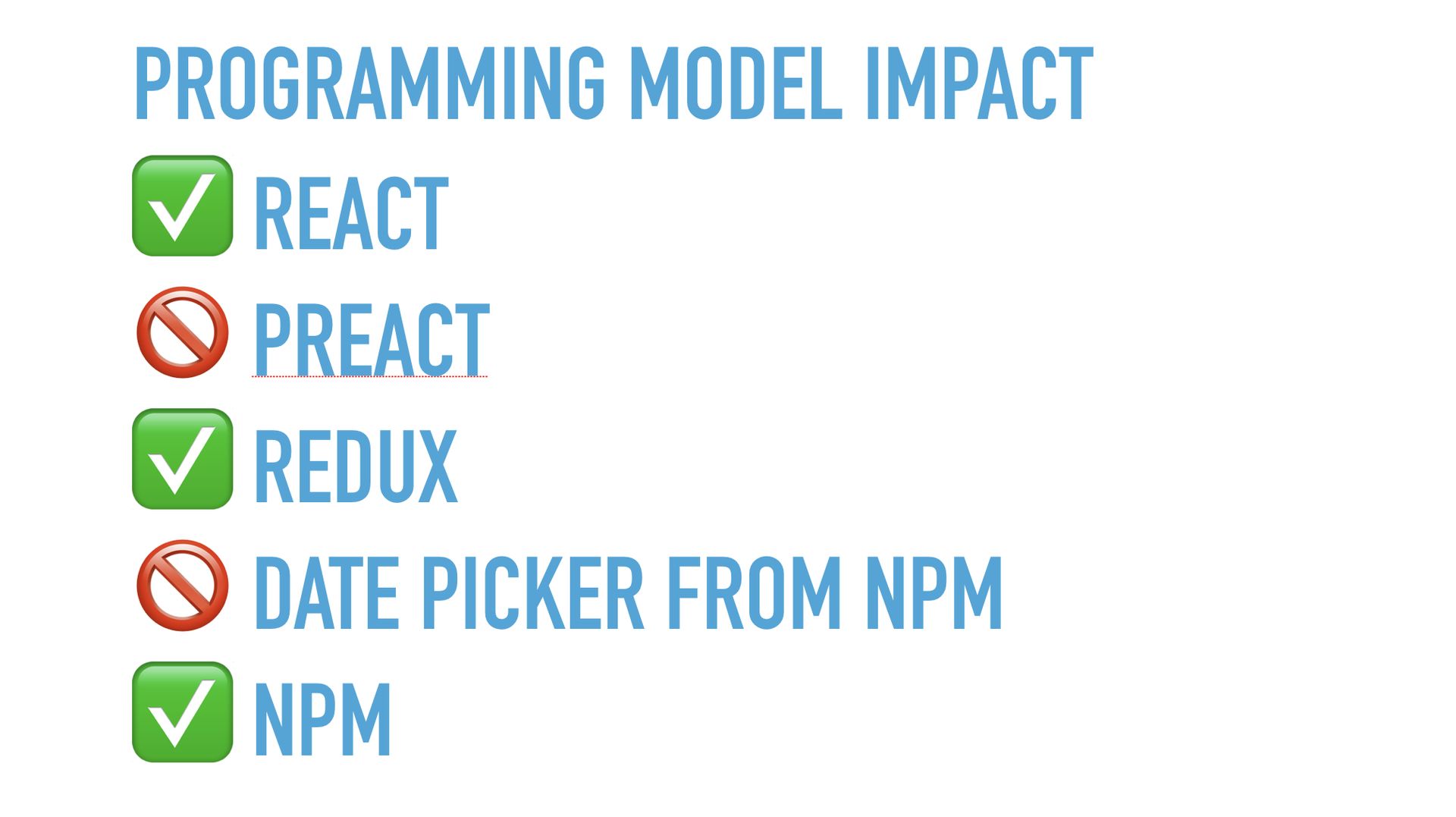

I want to give a few examples of things that impact the programming model: Let’s say you have an Angular project and you say “I’m going to port this to React” that is obviously going to change how people write software, right? But then you’re like “Ah, 60KB for a bit of virtual DOM munging, let’s switch to Preact”–that is an API compatible library, it is not going to change how people write software, just because you make that choice. Maybe then you’re like “this is all really complex, I should have something orchestrating how my application works, I’m going to introduce Redux.”–that is going to change how people write software. You then get this requirement “we need a date picker” and you go to npm, there are 500 results, you pick one. Does it really matter which one you pick? It definitely won’t change how you write software. But having npm at your fingertips, this vast collection of modules, having that around absolutely changes how you write software. Of course, these are just a few examples of things that might or might impact how people write software.

Now I want to talk about one aspect that all large JavaScript applications have in common, when you deliver them to users: Which is that they eventually get so big that you don’t want to deliver them all at once. And for this we’ve all introduced this technique called code splitting. What code splitting means is that you define a set of bundles for your application. So, you’re saying “Some users only use this part of my app, some users use another part”, and so you put together bundles that only get downloaded when the part of an application that a user is actually dealing with is executed. This is something all of us can do. Like many things it was invented by the closure compiler–at least in the JavaScript world. But I think the most popular way of doing code splitting is with webpack. And if you are using RollupJS, which is super awesome, they just recently added support for it as well. Definitely something y’all should do, but there are some things to think about when you introduce this to an application, because it does have impact on the programming model.

You have things that used to be sync that now become async. Without code splitting your application is nice and simple. There is this one big thing. It starts up, and then it is stable, you can reason about it, you don’t have to wait for stuff. With code splitting, you might sometimes say “Oh, I need that bundle”, so you now need to go to the network, and you have to factor in that this can happen, and so the applications becomes more complex.

Also, we have humans entering the field, because code splitting requires you to define bundles, and it requires you to think about when to load them, so these humans, engineers on your team, they now have to make decisions what is going into which bundle and when to load that bundle. Every time you have a human involved, that clearly impacts the programming model, because they have to think about such things.

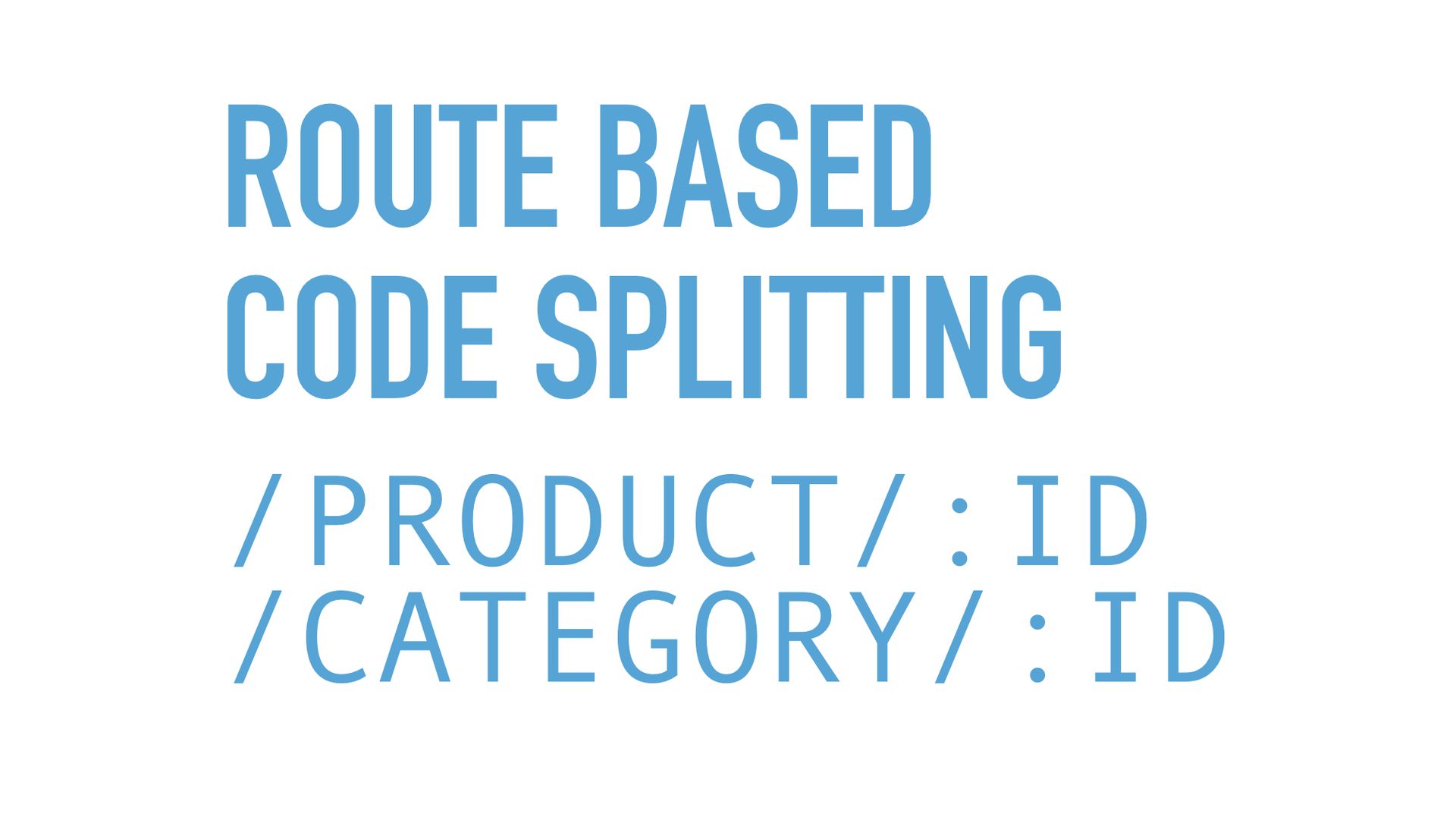

There is one very established way that solves this problem, that gets the human out of the mess when doing code splitting, which is called route based code splitting. If you’re not using code splitting yet, that is probably how you should do it as a first cut. Routes are the baseline URL structure of your application. You might, for example, have your product pages on /product/ and you might have your category pages somewhere else. You just make each route one bundle, and your router in your application now understands there is code splitting. And whenever the user goes to a route, the router loads the associated bundle, and then within that route you can forget about code splitting existing. Now you are back to the programming model that is almost the same as having a big bundle for everything. It is a really nice way to do this, and definitely a good first step.

But the title of this talk is designing VERY large JavaScript applications, and they quickly become so big that a single bundle per route might not be feasible anymore, because the routes themselves become very big. I actually have a good example for an application that is big enough.

I was figuring out how to become a public speaker coming up to this talk, and I get this nice list of blue links. You could totally envision that this page fits well into a single route bundle.

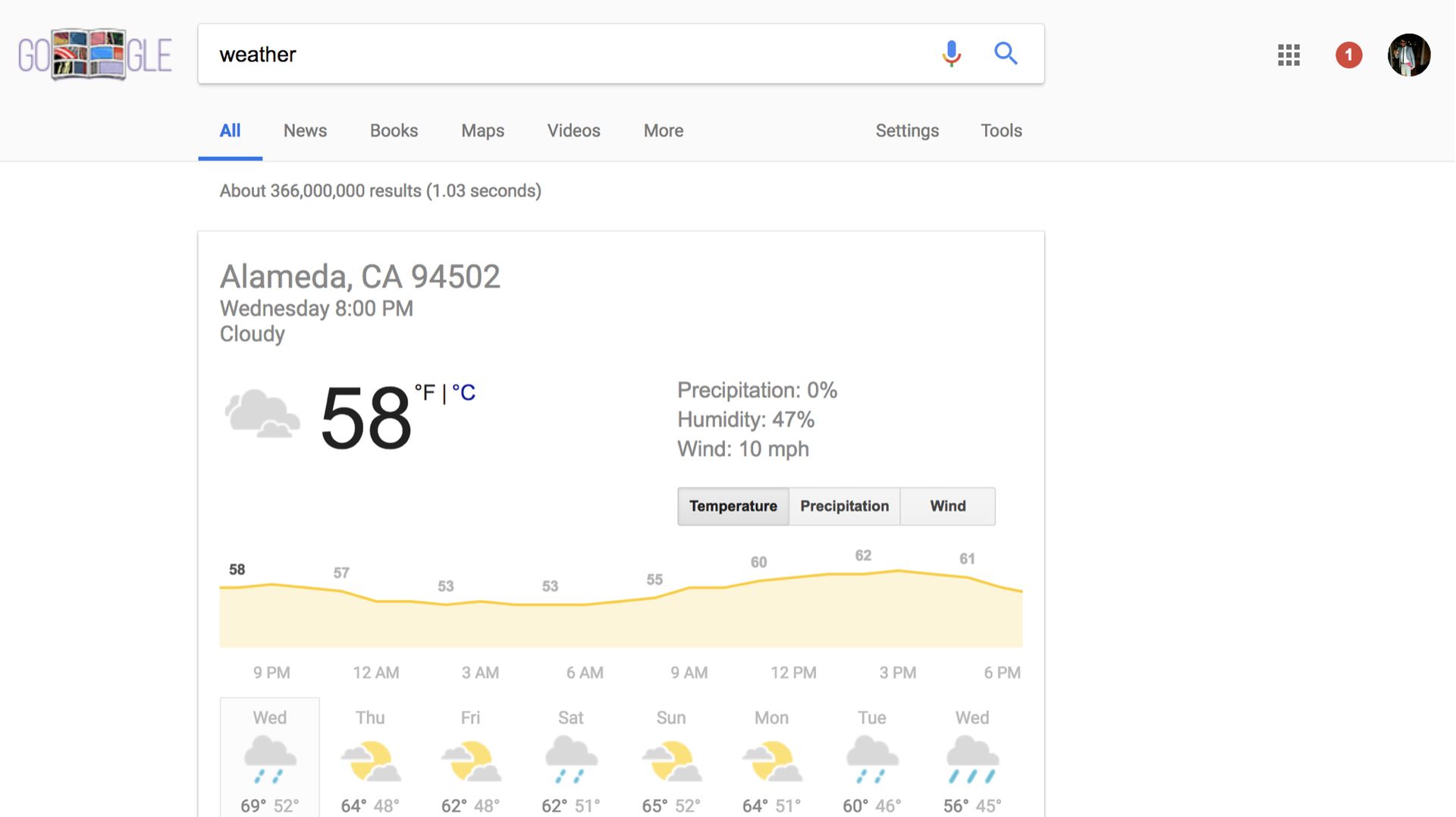

But then I was wondering about the weather because California had a rough winter, and suddenly there was this completely different module. So, this seemingly simple route is more complicated than we thought.

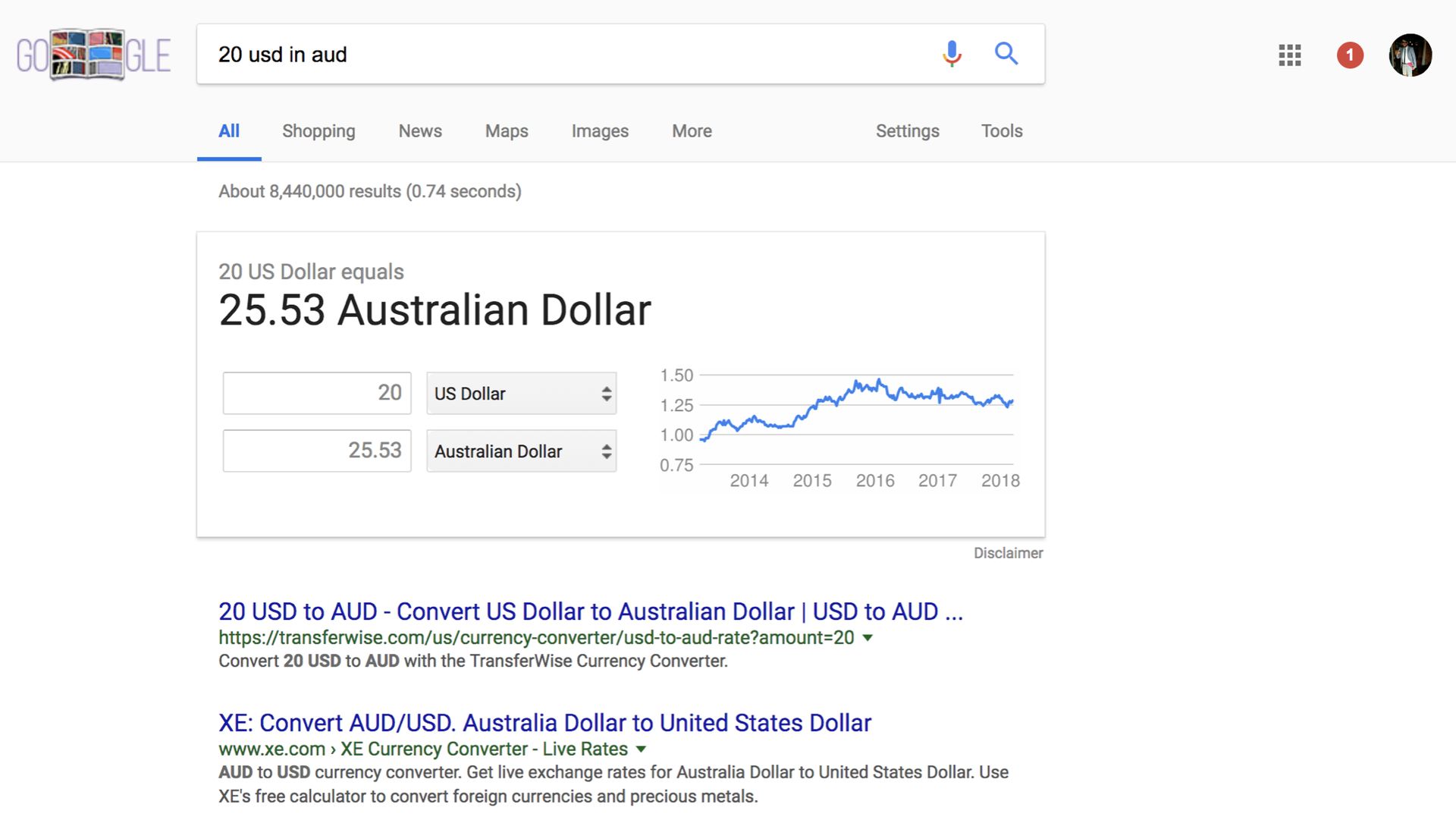

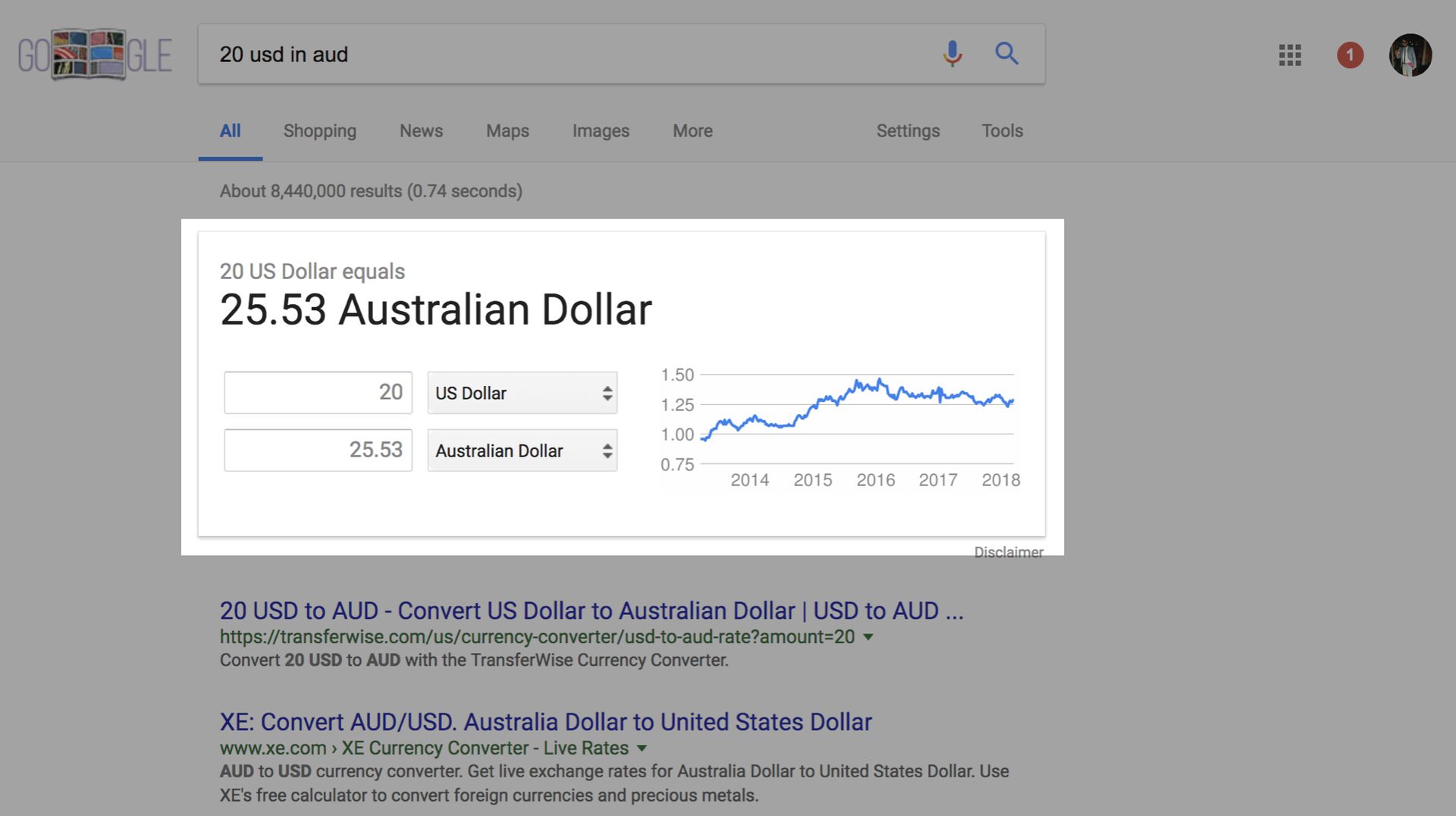

And then I was invited to this conference, and was checking out how much 1 US dollar is in Australian dollars, and there is this complex currency converter. Obviously there is about 1000s more of these specialized modules, and it infeasible to put them all in one bundle, because that bundle would be a few megabytes in size, and users would become really unhappy.

So, we can’t just use route based code splitting, we have to come up with a different way of doing it. Route based code splitting was nice, because you split your app at the coarsest level, and everything further down could ignore it. Since I like simple things, how about doing super fine-grained instead of super coarse-grained splitting. Let’s think about what would happen if we lazy loaded every single component of our website. That seems really nice from an efficiency point of view when you only think about bandwidth. It might be super bad from other point of views like latency, but it is certainly worth a consideration.

But let’s imagine, for example, your application uses React. And in React components statically depend on their children. That means if you stop doing that because you are lazy loading your children, then it changes your programming model, and things stop being so nice.

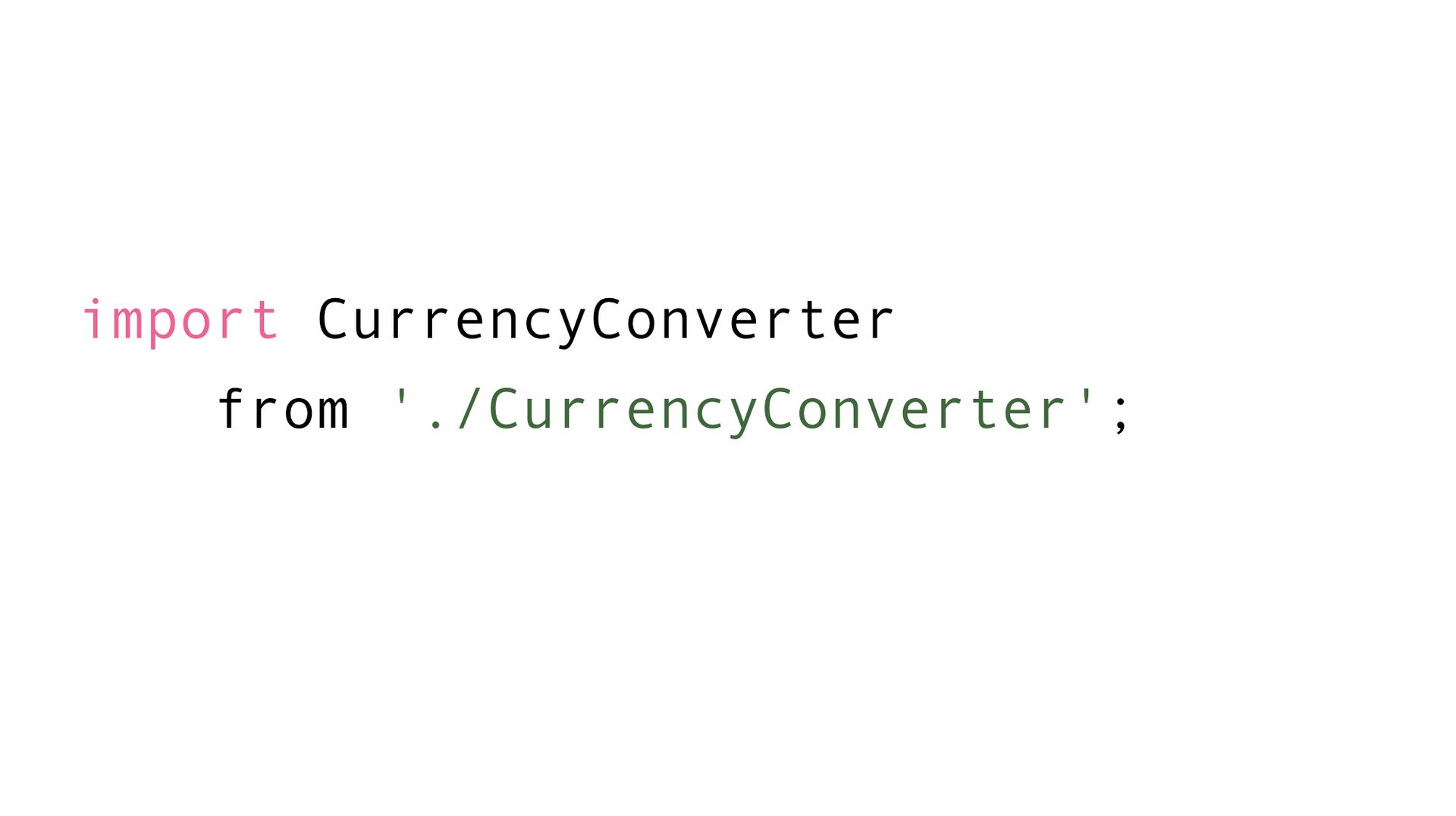

Let’s say you have a currency converter component that you want to put on your search page, you import it, right? That is the normal way of doing it in ES6 modules.

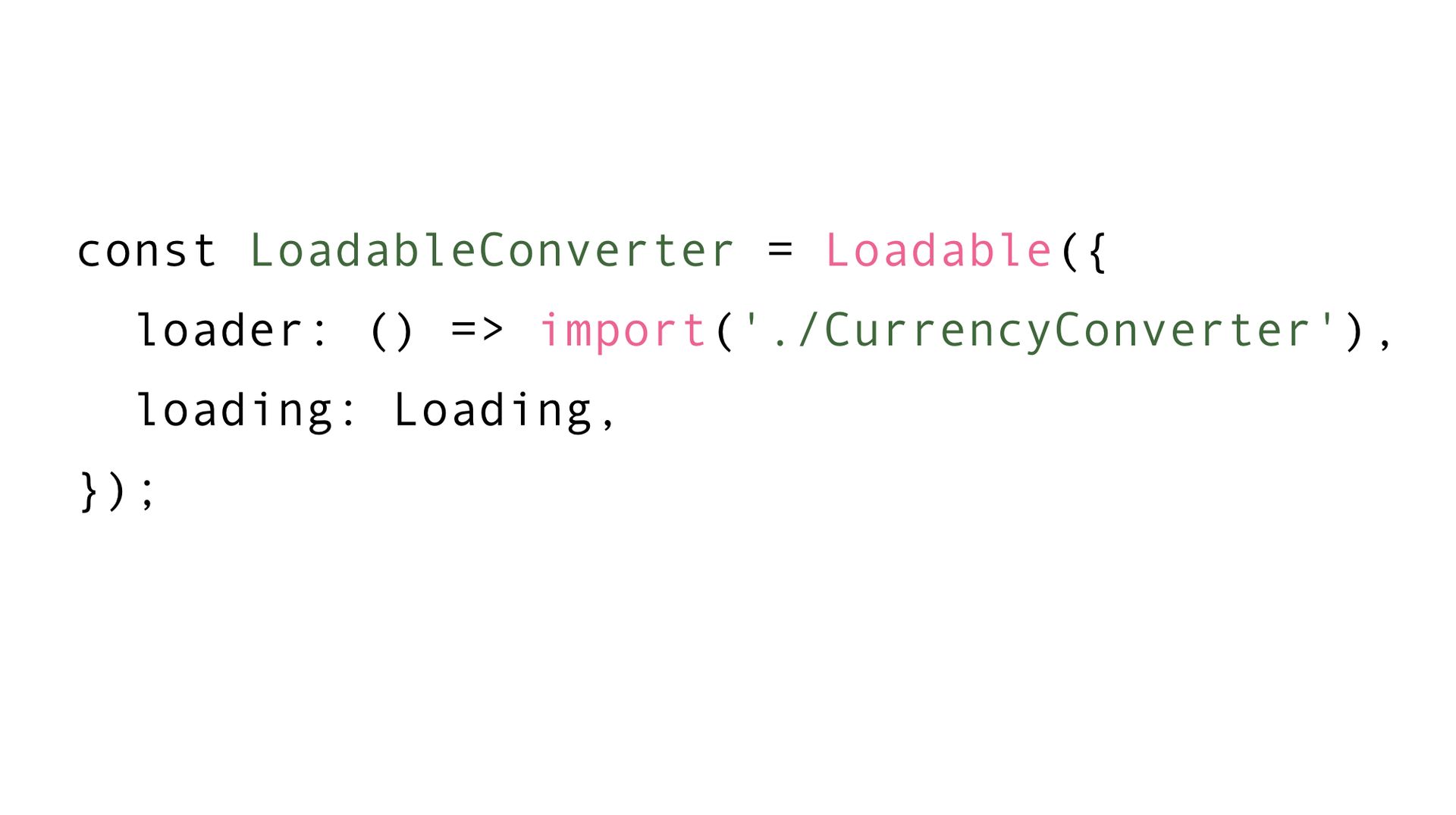

But if you want to lazy load it, you get code like this where you use dynamic import, which is a new fancy thing to lazy load ES6 modules and you wrap it in a loadable component. There are certainly 500 million ways to do this, and I am not a React expert, but all of these will change how you write the application.

And things aren’t as nice anymore–something that was static, now becomes dynamic, which is another red flag for the programming model changing.

You have to suddenly wonder: “Who decides what to lazy load when” because that is going to impact the latency of your application.

The human is there again and they have to think about “there is static import, there is dynamic import, when do I use which?”. Getting this wrong is really bad because one static import, when it should have been dynamic suddenly may put stuff into the same bundle that shouldn’t be. These are the things that are going to go wrong when you have a lot of engineers over long periods of time.

Now I’m going to talk about how Google actually does this and what is one way to get a good programming model, while also achieving good performance. What we do is we take our components and we split them by rendering logic, and by application logic, like what happens when you press a button on that currency converter.

So, now we have two separate things, and we only ever load the application logic for a component when we previously rendered it. This turns out to be a very simple model, because you can simply server side render a page, and then whatever was actually rendered, triggers downloading the associated application bundles. This puts the human out of the system, as loading is triggered automatically by rendering.

This model may seem nice, but it does have some tradeoffs. If you know how server side rendering typically works in frameworks like React or Vue.js, what they do is a process called hydration. The way hydration works, is you server side render something, and then on the client you render it again, which means you have to load the code to render something that is already on the page, which is incredibly wasteful both in terms of loading the code and in terms of executing it. It is a bunch of wasted bandwidth, it is a bunch of wasted CPU–but it is really nice, because you get to ignore on the client side that you server side rendered something. The method we use at Google is not like that. So, if you design this very large application, you have think about: Do I take that super fast method that is more complicated, or do I go with hydration which is less efficient, but such a nice programming model? You will have to make this decision.

My next topic is my favorite problem in computer science–which is not naming things, although I probably gave this a bad name. It is the “2017 holiday special problem”. Who here has ever written some code, and now it is no longer needed but it is still in your codebase? … This happens, and I think CSS is particularly famous for it. You have this one big CSS file. There is this selector in there. Who really knows whether that still matches anything in your app? So, you end up just keeping it there. I think the CSS community is at the forefront of a revolution, because they realized this is a problem, and they created solutions like CSS-in-JS. With that you have a single file component, the 2017HolidaySpecialComponent, and you can say “it is not 2017 anymore” and you can delete the whole component and everything is gone in one swoop. That makes it very easy to delete code. I think this is a very big idea, and it should be applied to more than just CSS.

I want to give a few examples of this general idea that you want to avoid central configuration of your application at all cost, because central configuration, like having a central CSS file, makes it very hard to delete code.

I was talking before about routes in your application. Many applications would have a file like “routes.js” that has all your routes, and then those routes map themselves to some root component. That is an example of central configuration, something you do not want in a large application. Because with this some engineer says “Do I still need that root component? I need to update that other file, that is owned by some other team. Not sure I’m allowed to change it. Maybe I’ll do it tomorrow”. With that these files becomes addition-only.

Another example of this anti-pattern is the webpack.config.js file, where you have this one thing that is assumed to build your entire application. That might go fine for a while, but eventually needing to know about every aspect of what some other team did somewhere in the app just doesn’t scale. Once again, we need a pattern to emerge how to decentralize the configuration of our build process.

Here is a good example: package.json, which is used by npm. Every package says “I have these dependencies, this is how you run me, this is how you build me”. Obviously there can’t be one giant configuration file for all of npm. That just wouldn’t work with hundreds of thousands of files. It would definitely get you a lot of merge conflicts in git. Sure, npm is very big, but I’d argue that many of our applications get big enough that we have to worry about the same kind of problems and have to adopt the same kind of patterns. I don’t have all the solutions, but I think that the idea that CSS-in-JS brought to the table is going to come to other aspects of our applications.

More abstractly I would describe this idea that we take responsibility for how our application is designed in the abstract, how it is organized, as taking responsibility of shaping the dependency tree of our application. When I say “dependency” I mean that very abstractly. It could be module dependencies, it could be data dependencies, service dependencies, there are many different kinds.

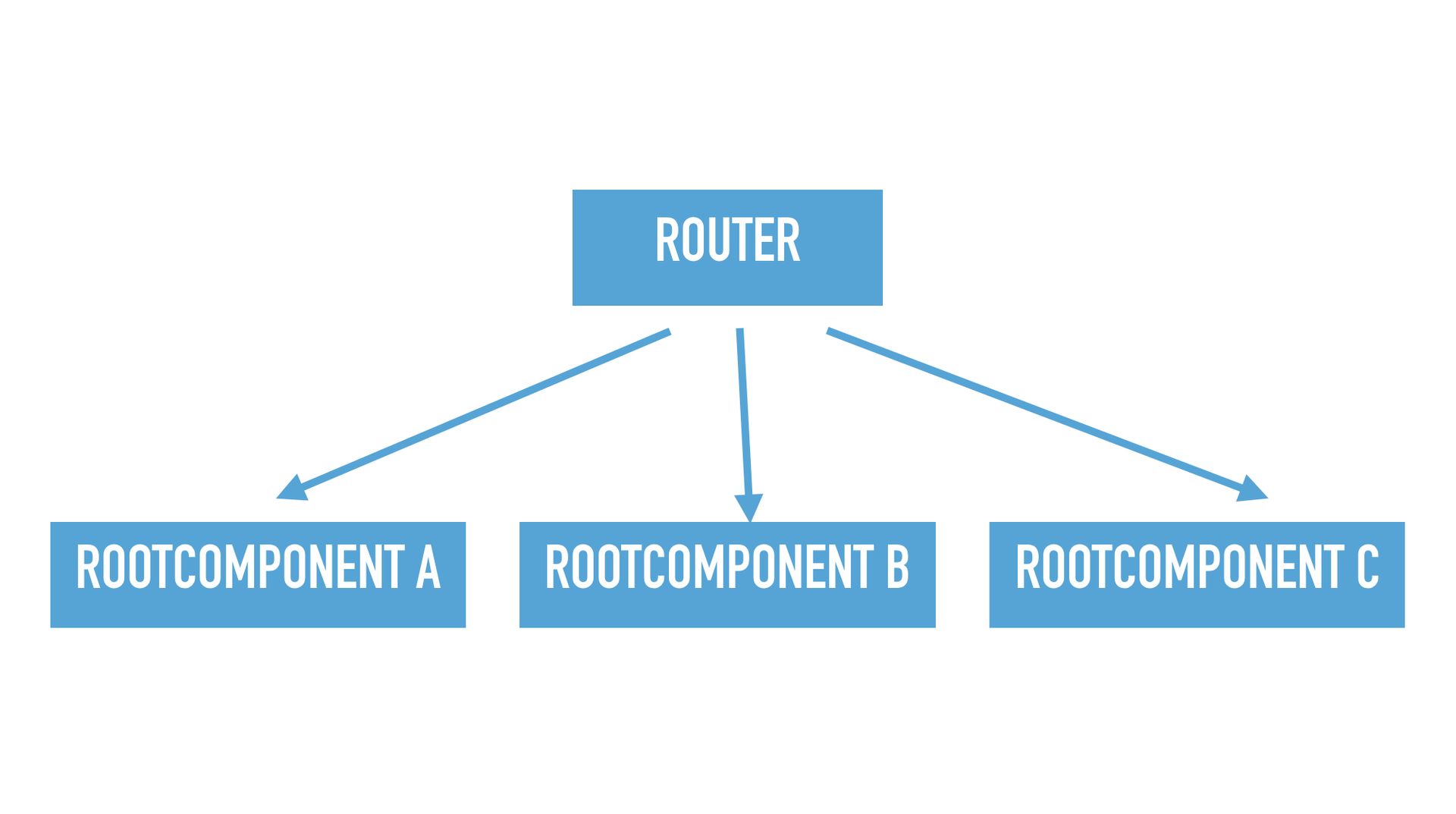

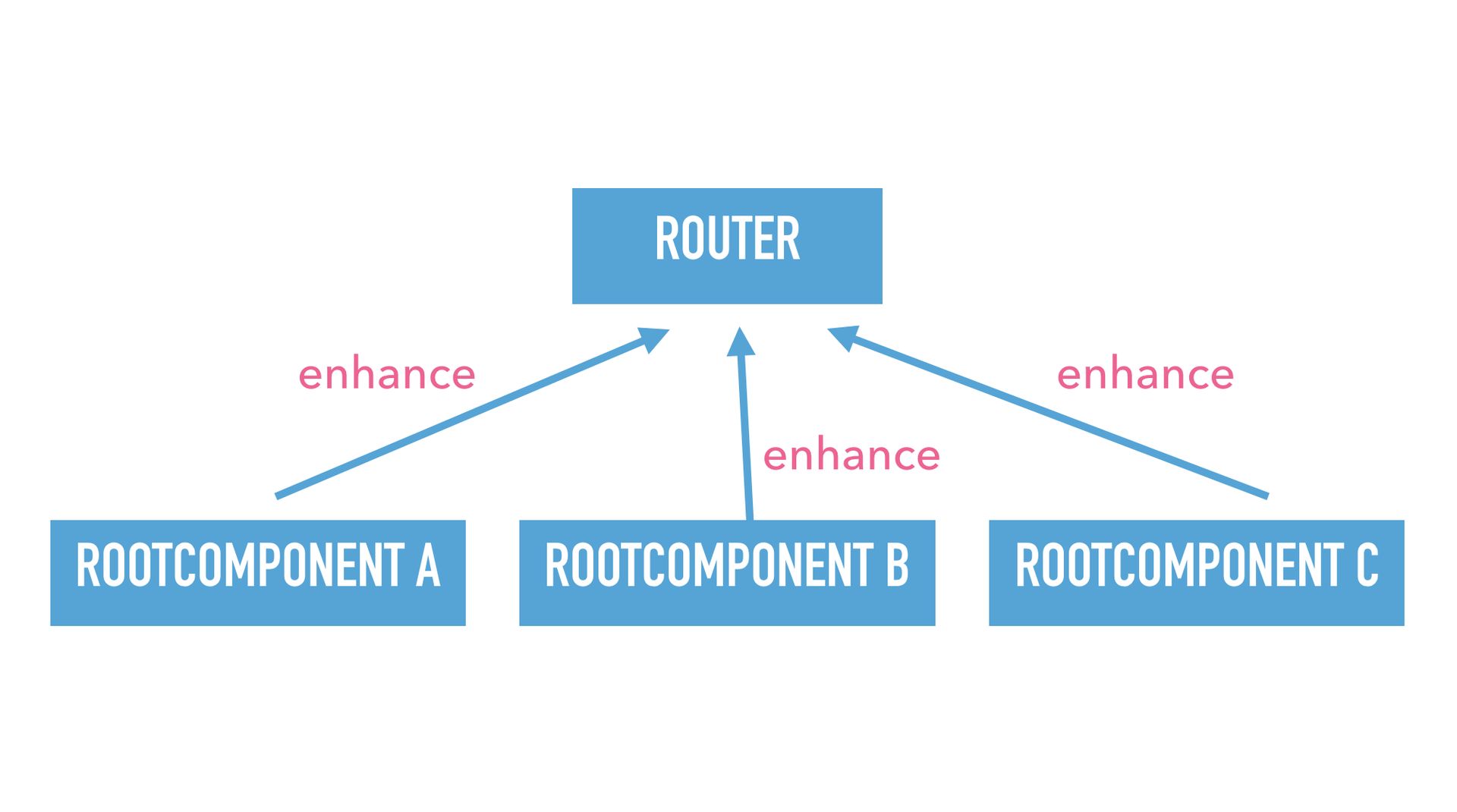

Obviously, we all have super complicated applications, but I’m going to use a very simple example. It has only 4 components. It has a router that knows how to go from one route of your application to the next, and it has a few root components, A, B, and C.

As I mentioned before this has the central import problem.

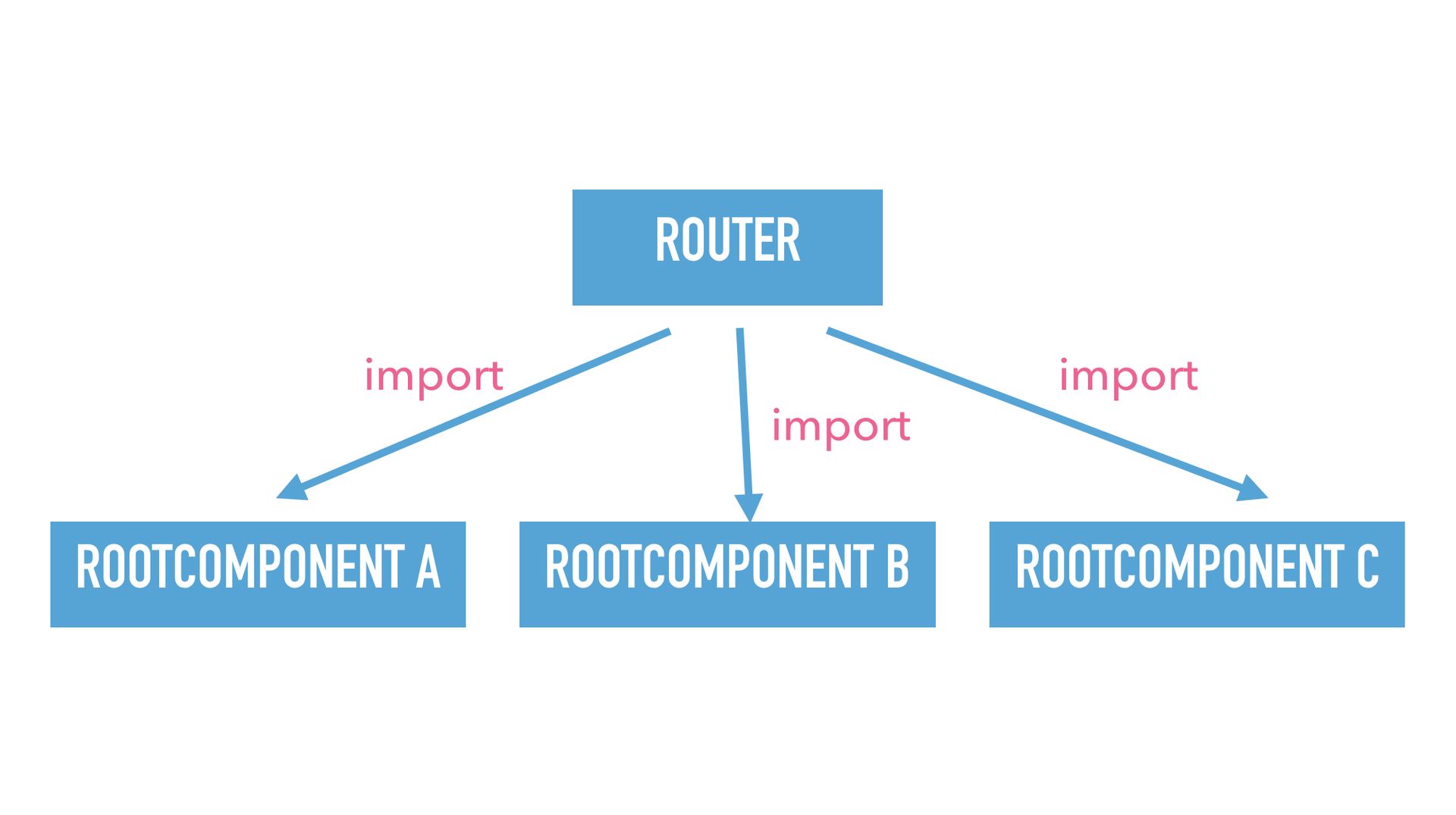

Because the router now has to import all the root components, and if you want to delete one of them you have to go to the router, you have to delete the import, you have to delete the route, and eventually you have the holiday special 2017 problem.

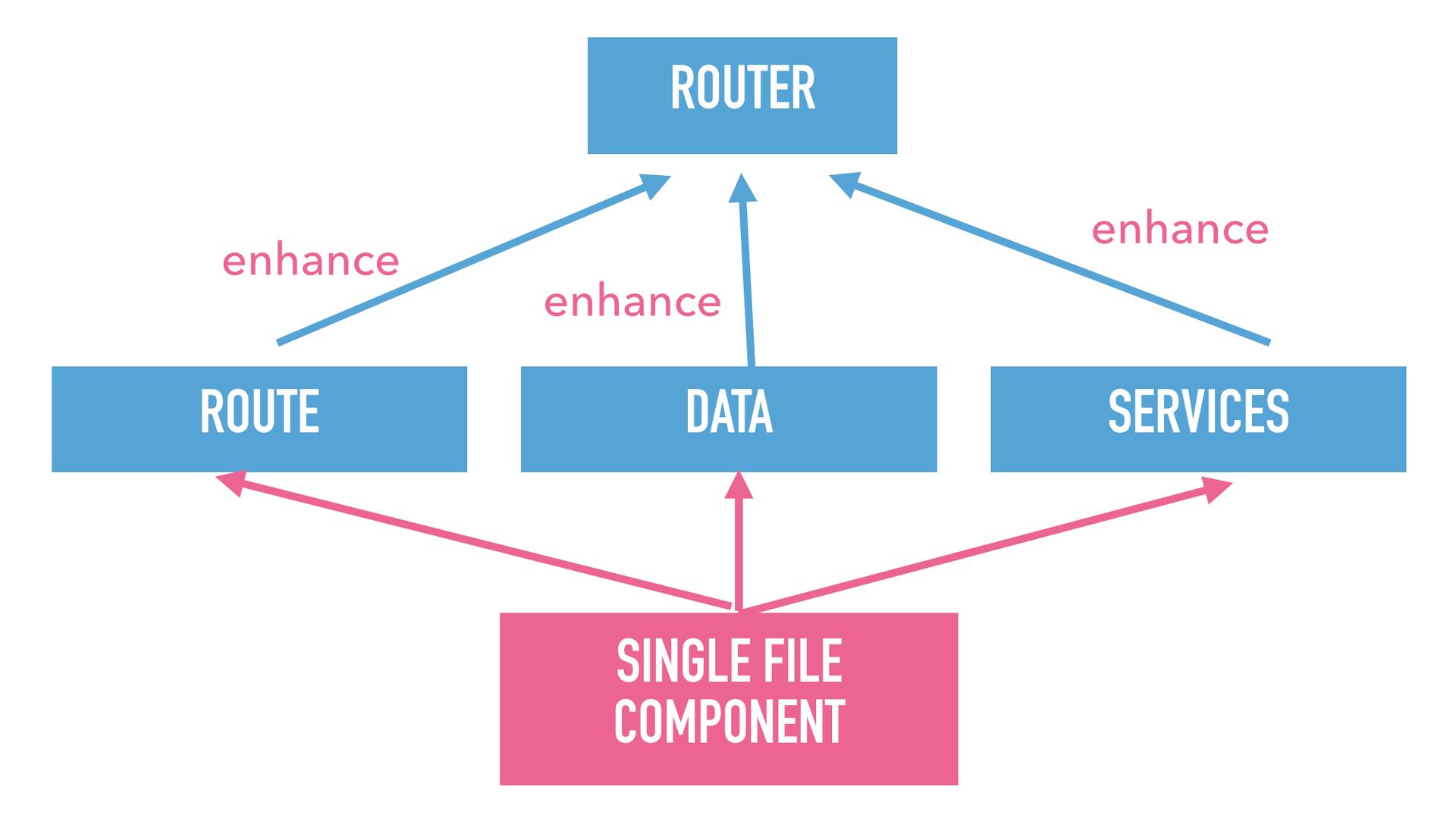

We at Google have come up with a solution for this, that I want to introduce to you, which I don’t think we have ever talked about. We invented a new concept. It is called enhance. It is something you use instead of import.

In fact, it is the opposite of import. It is a reverse dependency. If you enhance a module, you make that module have a dependency on you.

Looking at the dependency graph, what happens it that there are still the same components, but the arrows point in the opposite direction. So, instead of the router importing the root component, the root components announce themselves using enhance to the router. This means I can get rid of a root component by just deleting the file. Because it is no longer enhancing the router, that is the only operation you have to do to delete the component.

That is really nice, if it wasn’t for the humans again. They now have to think about “Do I import something, or do I use enhance? Which one do I use under which circumstances?”.

This is particular bad case of this problem, because the power of enhancing a module, of being able to make everything else in the system have a dependency on you is very powerful and very dangerous if gotten wrong. It is easy to imagine that this might lead to really bad situations. So, at Google we decided it is a nice idea, but we make it illegal, nobody gets to use it–with one exception: generated code. It is a really good fit for generated code actually, and it solves some of the inherent problems of generated code. With generated code you sometimes have to import files you can’t even see, have to guess their names. If, however, the generated file is just there in the shadows and enhances whatever it needs, then you don’t have these problems. You never have to know about these files at all. They just magically enhance the central registry.

Let’s take a look at a concrete example. We have our single file component here. We run a code generator on it and we extract this little route definition file from it. And that route file just says “Hey Router, here I am, please import me”. And obviously you can use this pattern for all kinds of other things. Maybe you are using GraphQL and your router should know about your data dependency, then you can just use the same pattern.

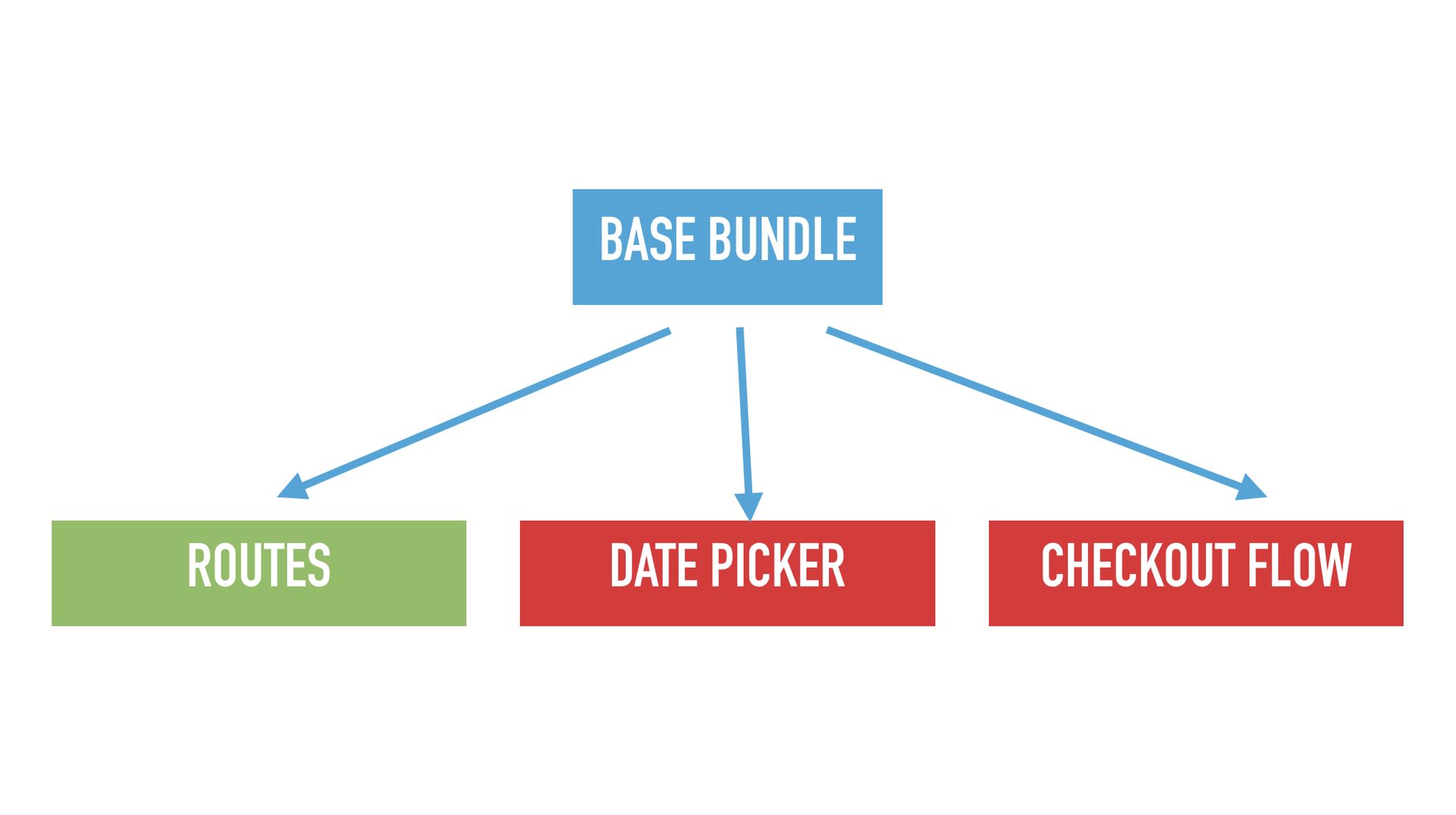

Unfortunately this is not all we need to know. There is my second favorite problem in computer science which I call the “Base bundle pile of trash”. The base bundle in your graph of bundles in your application is the one bundle that will always get loaded–independent of how the user interacts with the application. So, it is particularly important, because if it is big, then everything further down will also be big. If it small, then dependent bundles at least have a chance of being small as well. A little anecdote: At some point I joined the Google Plus JavaScript infrastructure team, and I found out that their base bundle had 800KB of JavaScript. So, my warning to you is: If you want to be more successful than Google Plus, don’t have 800KB of JS in your base bundle. Unfortunately it is very easy to get to such a bad state.

Here is an example. Your base bundle needs to depend on the routes, because when you go from A to B, you need to already know the route for B, so it has to always be around. But what you really don’t want in the base bundle is any form of UI code, because depending on how a user enters your app, there might be different UI. So, for example the date picker should absolutely not be in your base bundle, and neither should the checkout flow. But how do we prevent that? Unfortunately imports are very fragile. You might innocently import that cool util package, because it has a function to make random numbers. And now somebody says “I need a utility for self driving cars” and suddenly you import the machine learning algorithms for self driving cars into your base bundle. Things like that can happen very easily since imports are transitive, and so things tend to pile up over time.

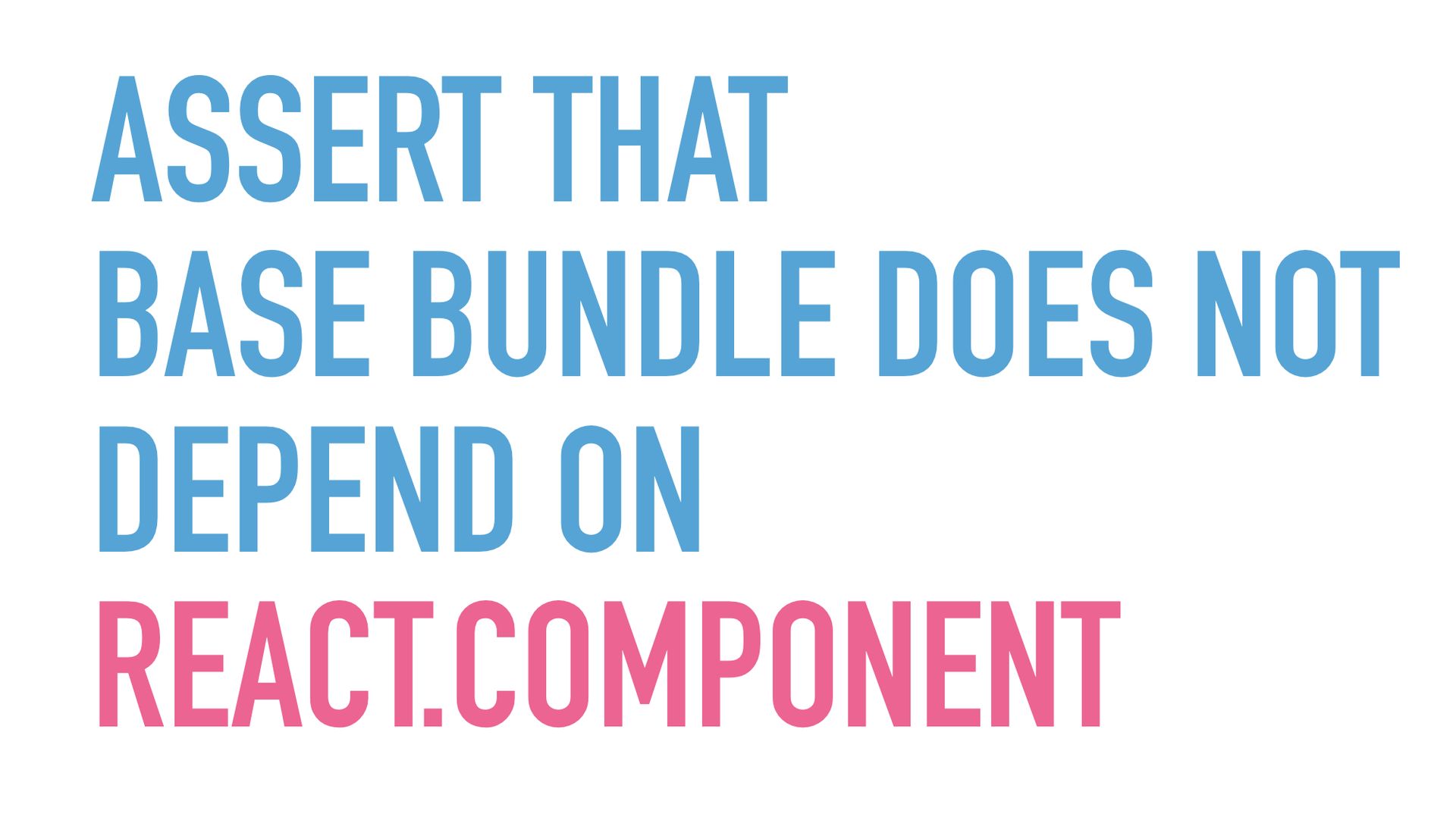

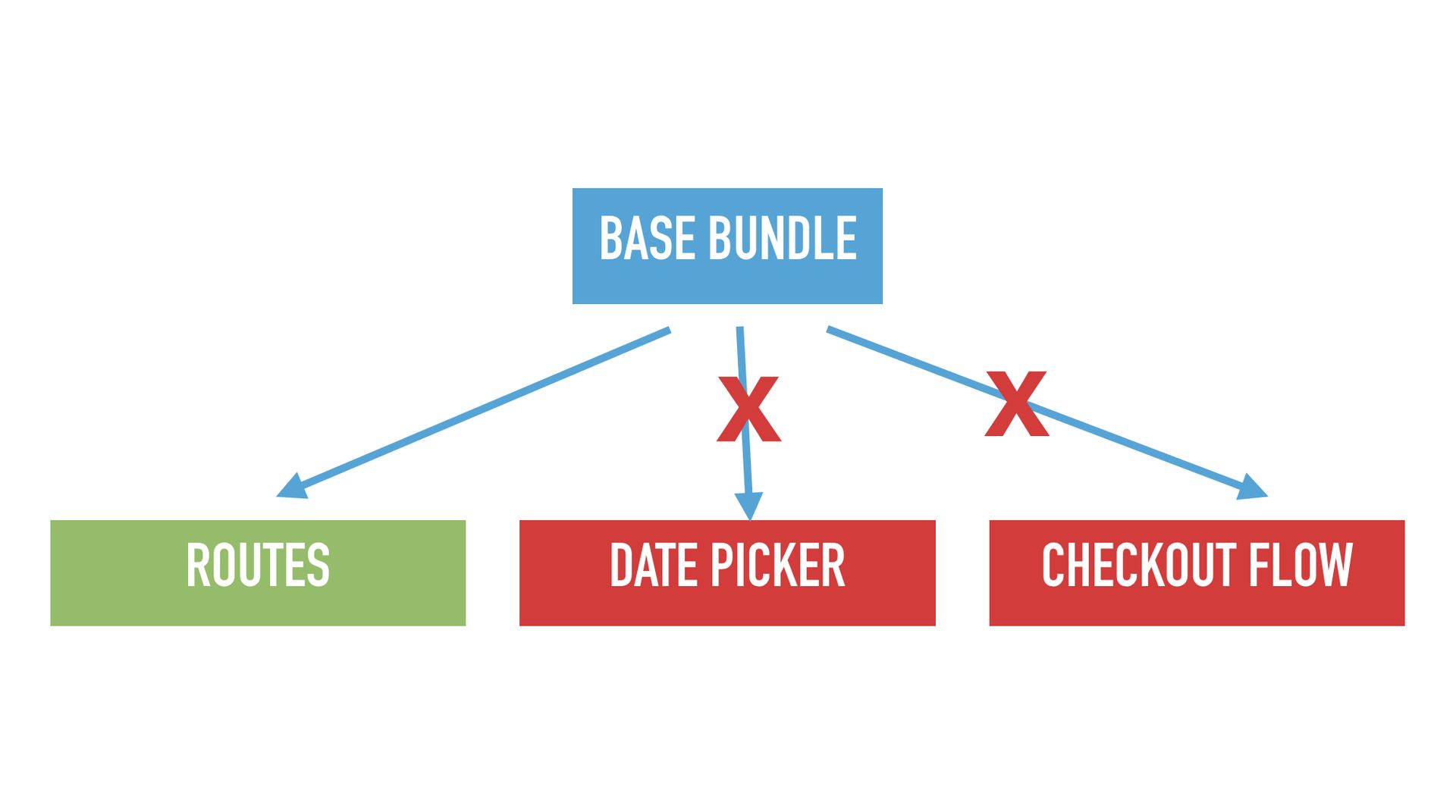

The solution we found for this are forbidden dependency tests. Forbidden dependency tests are a way to assert that for example your base bundle does not depend on any UI.

Let’s take a look at a concrete example. In React every component needs to inherit from React.Component. So , if your goal is that no UI could ever be in the base bundle just add this one test that asserts that React.Component is not a transitive dependency of your base bundle.

Looking at the previous example again, you just get a test failure when someone wants to add the date picker. And these test failures are typically very easy to fix right then, because usually that person didn’t really mean to add the dependency–it just crept in through some transitive path. Compare this to when this dependency would have been around for 2 years because you didn’t have a test. In those cases it is typically extremely hard to refactor your code to get rid of the dependency.

Ideally though, you find that most natural path.

You want to get to a state where whatever the engineers on your team do, the most straightforward way is also the right way–so that they don’t get off the path, so that they naturally do the right thing.

This might not always be possible. In that case just add a test. But this is not something that many people feel empowered to do. But please feel empowered to add tests to your application that ensure the major invariants of your infrastructure. Tests are not only for testing that your math functions do the right thing. They are also for infrastructure and for the major design features of your application.

Try to avoid human judgement whenever possible outside of the application domain. When working on an application we have to understand the business, but not every engineer in your organization can and will understand how code splitting works. And they don’t need to do that. Try to introduce these thing into your application in a way that is fine when not everybody understands them and keeps the complexity in their heads.

And really just make it easy to delete code. My talk is called “building very large JavaScript applications”. The best advice I can give: Don’t let your applications get very large. The best way to not get there is to delete stuff before it is too late.

I want to address just one more point, which is that people sometimes say that having no abstractions at all is better than having the wrong abstractions. What this really means is that the cost of the wrong abstraction is very high, so be careful. I think this is sometimes misinterpreted. It does not mean that you should have no abstractions. It just means you have to be very careful.

We have to become good at finding the right abstractions. #

As I was saying at the start of the presentation: The way to get there is to use empathy and think with your engineers on your team about how they will use your APIs and how they will use your abstractions. Experience is how you flesh out that empathy over time. Put together, empathy and experience is what enables you to choose the right abstractions for your application

If you found this interesting, consider reading my article on design documents or the sequel to this post “Designing Even Larger Applications”.

Published