This is a mildly edited transcript of my JSConf Hawaiʻi talk (video).

Hey everyone! My name is Malte, I’m a Principal Software Engineer at Google, and today I want to talk about Designing Even Larger Applications. This is a sequel to a talk I gave at JSConf Australia two years ago. And just like last time, I want to kind of ground this talk in our career progression as software engineers. I think many of you in the audience would call yourself senior engineers; or, if you’re not there yet, you aspire to be one.

The way I would describe what it means to be a senior engineer is that if someone comes to me and they say something like “Hey, Malte, do this project in this domain that you are already familiar with”, I would say “Yeah, that is actually something I know how to do. I don’t need to get anyone else’s help”.

In my last talk I looked at how to go beyond that level of seniority in software engineering. It stops being only about yourself and instead your craft starts impacting other engineers. You’d say “I can anticipate how others do things and design APIs accordingly.”

In this talk I want to go yet one more level beyond that. I want to reach the stage where I can say, “I can design software such that for large groups of engineers the probability increases that the software that they produce is good.”

There are three key words in this statement.

First of all, large groups of engineers. If you work at a startup or a three-person company, then this talk may seem superfluous and boring. But I think many of you may work for insurance companies, banks, agencies, big tech, etc.–companies big enough that you have a bunch of folks and multiple teams and you need to coordinate stuff.

Next I’m talking about probability. There is no certainty here. You can only try to set things up so that they are likely to work. But there are no guarantees. There is no silver bullet.

The third key word is good. This is not a product management talk. This is not a talk that will not help you write the right program, but it will help you write that program well. What I mean is it being maintainable, high-performance, having low bug-density, being delivered on-time, etc.

I want to clarify one more thing: I’m going to say the words framework and software infrastructure a lot. I treat them kind of interchangeably. What I mean is software that helps us build better software. For this talk, I would like you all to kind of put your mind into you being the person in your company who is responsible for defining how people write software and, then, build the infrastructure that they’re using to write software. And when I say, you build a framework, I don’t mean that you necessarily make your own React or Angular. Instead I think whenever you have a set of teams you want to kind of standardize how they build applications. So, you put a literal framework around it.

Again, think about you being the person who is responsible for your team’s software infrastructure. This is a talk about how to make you successful at that job. And I’m going to talk about that in three chapters.

The first one I call understanding the degree of uncertainty

…and then we’re going to learn how to solve all known problems.

Finally, we’re going to learn about deploying change.

Understanding the degree of uncertainty #

How certain are we about the type of problems that we will need to solve in the future? This question is absolutely key for software engineering and I’m going to talk about a technique to understand how well we understand things.

What we’ll do is try to answer a set of questions:

What is it in the existing infrastructure that users struggle with and how are they struggling with it?

What is the class of applications that folks will build using your work in broad terms?

What are the trends that influence the industry and how do those trends influence the software that folks are probably going to write in the future?

All of these may sound a bit like reading the tea leaves but I think that with a bit of experience there are many scenarios where you can actually answer them quite well. The key in this exercise is really to observe how easy or hard it is to answer the questions.

If it is really easy and you write it down and everything is clear, then you have a low degree of uncertainty. If, however, you actually have no idea how to answer, then you have a high degree of uncertainty.

Even more powerful than knowing what it is that you need to do is knowing what you don’t need to do. Those are the non-goals.

What are non-goals? It is not a non-goal if you’re working for a software company to say “I don’t need to design surfboards”. That is not a non-goal, that is just ridiculous. Of course, you don’t want to do this. A non-goal is something that is actually super reasonable and even likely that you want to do it but you know you don’t need to do it (like “I need to support low-end devices”). If you can easily define your non-goals, you know that your degree of uncertainty is even lower.

So, why is it important for the degree of uncertainty to be low? When uncertainty is high you’re going to have to make tradeoffs and be flexible. You may think “I might need to support this special case so I better make sure that it would be possible”. You likely need to make a tradeoff to enable that special case. And the problem with tradeoffs is that they make stuff complex and less than ideal because you have to find the balance between conflicting concerns.

Things really get unpleasant when a high degree of uncertainty leads you to make an unnecessary tradeoff.

Unnecessary tradeoffs are the root of all evil. #

Let’s look at an example: imagine you’re building infrastructure for internal mobile apps at your company and maybe the salespeople all have old phones with low memory. Based on this you design things such that they work on low memory devices. But then your company goes out and buys everyone fancy new phones. All your work to support low-end devices was unnecessary, and even worse it probably made the software more complex in the future as well. Interestingly this is a generalization of Donald Knuth’s “premature optimization is the root of all evil”. Premature optimization is a special case of an unnecessary tradeoff. Every time you design your software for something it didn’t really need to support that is likely an unnecessary tradeoff.

This talk is being held at a web development conference, so I wanted to have one section on web development. We as a community have been building web frameworks for a few years. Over 20 years now. We actually understand how to build web frameworks really well. The degree of uncertainty for what people want to do with web frameworks is really low.

Compare that to this scenario: imagine it is 2015 and your manager comes and says “I want you to build infrastructure for deep learning”. You’re like, well, I have never done this before. No one in my company has done it before. There are like literally three blog posts on the topic in total. The degree of uncertainty is really high. You won’t be able to build infrastructure that is quite as nice as a web framework in 2020.

Dealing with uncertainty #

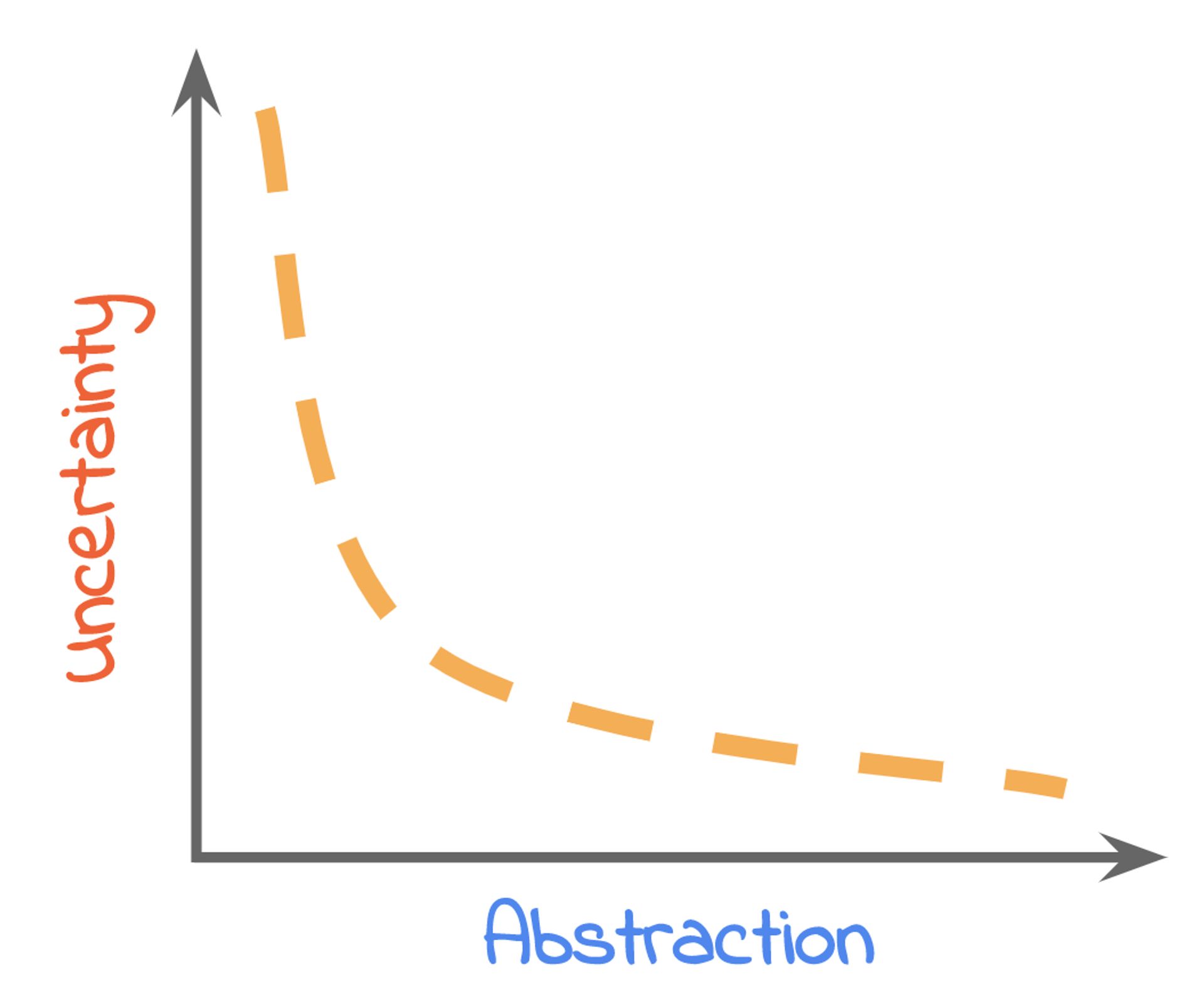

And so the question is: what do we do if the degree of uncertainty is very high? We tailor the degree of abstraction.

Let me get something out of the way: abstractions are awesome. You want to abstract everything as much as possible because abstractions make everything really expressive, more correct, reusable, and generally, more awesome. However, things rapidly fall apart if the abstractions don’t quite allow us to do exactly what we’d like to do. We now have to work around it and beat them into doing what we want. Everything is suddenly painful and terrible.

If uncertainty is high then reduce the degree of abstraction. #

That is why we need to understand the problem space really well: It allows us to tailor the abstraction to the degree of uncertainty. And if uncertainty is high then we reduce the degree of abstraction.

Solving all known problems #

Every software project is going to have some degree of uncertainty. And so it is useful to have a set of techniques in our back pocket that are always good–no matter how uncertain we are: we’ll solve all known problems of software engineering.

Iteration velocity #

The first technique is optimizing iteration velocity. What I mean is: you write some code and hit save in your editor–how long does it take to go from that moment until you find out whether it was a good change? You might have super awesome hot code reloading and everything updates instantly like magic or you may need to manually kill your Java application server, recompile, and restart the server which takes like 20 minutes. I think many of us have probably been somewhere in between these two extremes.

Slow iteration cycles actually introduce tradeoffs into our software design. If it takes a long time to find out that you made a mistake then as a software designer, the professional thing to do is to then go and say “I have to design this API so that no one can ever get it wrong”. If on the other hand everything is super fast and folks can figure things out iteratively because the cost of failure is so low, then you as a designer of that API can say, maybe it is fine for people to do a little bit more exploring here.

Debuggability #

Next is debuggability. As a framework author we actually have a strong influence on how hard it is to debug a system. Maybe you designed this awesome but complex black box state machine that no one can figure out. Maybe your stack traces are super long and confuse people. Or maybe you put in a sensible logging and tracing system and people understand what is going on. They make a mistake, they debug it, they fix it. No problem.

Testability #

Similar to the debuggability you’re in control of how testable a system is. Maybe your framework makes it really hard to instantiate things to be in a given state that can be tested? Or you make that really easy. Folks will write more tests, have higher confidence, and be a happier customer of your framework.

Empathy #

For the last technique to solve all known problems of software engineering we’ll move a little bit away from the pure software side of things. We’ll talk about empathy.

And like I mentioned in my last talk: As a software engineer having empathy with other software engineers is empathy in easy mode. Our intuition for how a software engineer feels about something is much more likely to be correct than with a random person where we know little about their background. Today I want to talk about a very special aspect of empathy: You as the designer of framework could build the perfect application with it. You know everything about it. You can get everything right. But every other person who uses your framework will know less about it.

Think about what it means to not know everything about your framework. #

So, think about what it means to not know everything about your framework. And how you can make the framework be robust in the presence of such not-all-knowing users.

Deploying change #

Now that we have learned to solve all known problems of software engineering, let’s go to the final chapter which is deploying change.

If it has no users then it has no impact. #

This part is really, really key. Software infrastructure, no matter how great it is, if it has no users then it has no impact. However, in this field it is incredibly common that people build ivory towers with no real users in mind. They build something they’re excited about, and it was probably really fun to build. And then they come and say “Hey, I have a thing” and you’re like “But that thing doesn’t do what I need” and everyone is sad and they move on to build the next ivory tower.

If you want to professionalize building software infrastructure then this is obviously not the right way to do it. Getting your stuff adopted is everything. It is a big part of your job. So much so that my first piece of advice on how to get this right is actually totally in the realm of marketing.

Software engineers are human beings. They want to work on stuff that they think is cool and that they’ve heard about on Twitter (Think “Serverless”, “Machine Learning”, “Virtual DOM”, $HypedThingOfTheYear). I think it is fine to sprinkle some of that glitter into your framework. As long as it isn’t the worst unnecessary tradeoff in the world. Everyone will be a little happier and no harm is done. That was the marketing portion of this talk. Let’s go to a bit more serious topic.

Incremental adoption #

Adopting software is easier if you can do it incrementally. What this means is that instead of going like “Hey, try this new framework, rewrite everything from scratch in two years and hopefully it is good”, you migrate smaller parts step by step–and thus you see positive impact long before that 2 year full rewrite. What I’ve seen is that even projects that start out as a full rewrite will often pivot to ship at least a few parts early as the pressure from essentially having to do double-work (maintaining the legacy system and building the new one) increases and management wants to see results.

The path to incremental adoption, however, can be difficult for the framework designer. The following techniques have been proven to work in such scenarios.

Legacy composition #

The first technique is really simple and comes in two parts.

The first is composition of your new framework code into legacy code: Let’s say you haven’t gotten around to rewriting the app shell yet. The app is still built on the old architecture. But then the team comes and says, “I’m going to build that new feature based on the new framework and put it into that old code base”. That is composition of new code into legacy code.

And then there is the other side which is composition of legacy code into your new code base. Let’s say you have this super ultra-customized component, a jQuery date picker, and people want to keep it, right? And so you design your framework such that the jQuery thing, which probably violates all the assumptions you ever made, still works in your new code base. That is composition of legacy code into new code.

Both of these strategies put tradeoff pressure on your system because suddenly all these assumptions are no longer valid. But the tradeoff is probably worth it because it allows people to incrementally adopt your software.

Temporary imperfection #

The second technique is what I call temporary imperfection. As a framework author, you probably have this really idealized view of the world how people build software using your framework. But then it comes crashing down in the process of incremental adoption because not everything is ideal at all, but rather an entangled mess of old and new code.

My advice would be to do the following: Write a literal lint rule using a tool like ESLint that identifies the old way of doing something. And then when there is code in the code base that is not written to the new way, you get an error message. Hopefully the error message also says something helpful like “This is no longer the right way of doing it. Here are pointers to documentation for how to do it right”.

Step two is to then go and allow all existing violations using an allow-list. With that you’re in a position where no code is fixed, but where all new code has to comply with the new way of doing things. And this is really powerful because there might be all these engineers in the organization who have not read the email where they were told they need to do something differently. Now they get an error message and will just turn around and fix it.

A ledger of technical debt #

There is one more interesting insight. This allow-list which you check into your repository is, in fact, a ledger of technical debt. Technical debt can be this abstract concept that you know you have. It is probably out there somewhere but it is really difficult to nail down where it is. The ledger allows you to literally know that file X.js, line 15 has technical debt in it.

Knowing where the technical debt is, is the first step to paying it off. You can e.g. have a team fix-it where all you do is make the allow-list shorter. I think that is a powerful way to make tech debt very concrete just like debt from your bank account.

Automated migration #

The next technique is to enable automated migration. It is not going to get you all the way but it is pretty powerful. Tools like codemod from Facebook can help with such a process. You declare how to go from A to B and the computer does the rest of the work. It is great.

As many things in this talk, designing for automated migration puts tradeoff pressure on your new API because now your new API must ideally only require information that is already available in the existing codebase. But it might be worth it because no one has to do that work manually and it is going to make people more happy than having to do everything by hand.

Customer Zero #

Let’s talk a little bit more about humans. The one thing I would like everyone to take away from this talk is that when you’re in this role of being the person responsible for the software infrastructure, you always need a customer zero. Your customer zero is the antidote to the ivory tower. They are your first customer and you’ll be helping them to build a real product.

Your customer zero is the antidote to the ivory tower. #

What you need to do is go and literally write their software with them–become part of their team. This is all happening before you declare your framework to be shippable because in this step you can actually validate your assumptions. You can find corner cases and you can iterate on your framework until it is actually good. This first customer should not be a migration. It should be something that you built from scratch. Because migrations are always going to be somewhat painful and long winding and you really don’t want to migrate to something that hasn’t been proven to be good.

One of the ironies of being an infrastructure engineer is that you rarely build anything with your infrastructure yourself. That makes it really difficult to actually write the documentation for how to get started with your infra. If you go and have a customer zero and you work with them, that is the best chance you get to write that onboarding doc for everyone who comes after. Don’t miss the chance!

Actually finding a customer zero can be challenging in large organizations. You might not find the team that is cool with working with an unstable framework that might be pretty bad. I’ve found a few arguments that work well to convince a team to be your customer zero:

There is typically a team that likes to be on the cutting edge. One of the things that you can pitch is to say “Hey, you’ll eventually have to migrate to this because it is the future stack everyone will have to use. Why don’t you want to be on the new thing already and skip that migration?”. That could be very attractive for a team. And you can argue that because you’re actually going to work with the team, they are going to get a framework tailor made for them–as opposed to everyone else who will have to make do with what is there.

If that pitch doesn’t work, you’ll have to move on to harsher tactics. In that case the organization has to be mature enough to accept that you’ll have to have a mandate. Someone will have to decide which team is going to be customer zero and they’ll have to accept it. Because the alternative is that you’d build an ivory tower. And that would be bad for everybody, not just that one team.

Migration Zero #

Eventually we’ll have to do a first migration of an existing code base to our new infra. Once again it is actually your job to do this migration yourself. That is because your framework might not actually be a great migration target yet. Let’s assume your framework is at point B and some project is at point A. It might be super hard to go from A to B. Any given team would probably just go ahead and do it anyway. But you as the author of the framework might see chances to slightly change that point B such that it is easier to get there. And because you’re a lazy person, you’re going to make that migration really easy and that is going to help everyone that comes after you have a much better time.

Summary #

These were the three things that I wanted to talk about. Just let me summarize really quickly:

The first thing that we need to do is to understand the degree of uncertainty and then tailor the degree of abstraction respectively.

Even if uncertainty is high, we want to solve all known problems: Increase iteration velocity, make things debuggable, testable and practice our empathy with a focus on what folks might not know.

And then finally, nothing here matters if you don’t focus on team adoption. Make your software likable, focus on incremental adoption, make a ledger of technical debt, and get that customer and migration zero done.

That is all I have today. Thank you very much.

Malte Ubl, 2020

Thanks to Esther, Ryan, and Jan for helping me copy-edit my verbal mess 🤣

Published